The European Commission support for the production of this publication does not constitute endorsement of the contents which reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

According to a 2018 Media Literacy Index report conducted by the Open Society Institute in Sofia, it was found that “Balkan countries are the most susceptible in Europe to ‘fake’ news – owing to their highly controlled media, low educational levels and low levels of trust in society.” [1] Every single country, not only in the Balkan region but worldwide, has had its own experiences with fake news and press freedom or the lack thereof but it all comes down to one thing – how is it being handled?

The main country of focus for this country-level analysis is the beautiful Republic of Albania. Being one of the most beautiful countries I have ever personally visited, full of rich and traditional culture, amazing food, a complex language with various dialects, and perhaps the strongest feeling of nationalism you have probably ever experienced, you might say Albania truly has it all. But, is this the case when it comes to fake news in Albania?

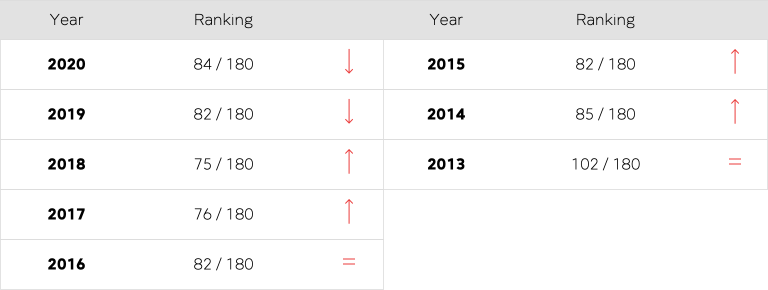

As of this year, Albania is currently ranked #83 in the 2021 World Press Freedom Index, positioned about average when compared to its neighboring countries. [2] Bordering Albania, Kosovo* is ranked #73, Montenegro is ranked #104, and Greece is ranked #70 [2]. Albania has seen a mix of increases and decreases over the past 8 years which can be seen in Table 1 below.

Table 1. Ranking since 2013 (Source: Reporters without borders)

Aside from Albania’s ranking when it comes to freedom of the press, the country has had its own issues with the handling of fake news and disinformation, many issues that are still avidly prominent today. In a 2021 study titled “Mapping Fake News and Disinformation in the Western Balkans and Identifying Ways to Effectively Counter Them”, Albania along with the rest of the countries in the Western Balkans were analyzed and key points related to Albania’s case were found which will be explained further on in the text [3].

Case Study #1: The Social Media Prime Minister

Dubbed “The Social Media Prime Minister”, Prime Minister Edi Rama is currently serving as the 33rd Prime Minister of Albania and he has had his fair share of run-ins with spreading disinformation for political purposes. Just like with every country, politicians are known for taking advantage of the people they are supposed to represent and protect by spreading disinformation and by discrediting the media but how does this help PM Rama in the long run?

In March 2020, what we know as the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, PM Rama was forced to make a public apology due to his role in the spreading of disinformation. His misconstrued views of a video made international headlines and caused tensions between Albania and Spain which could have been ultimately avoided if he and his team did their due diligence and fact-checked what was going on. “Rama was forced to make a public apology in March 2020 for fabricating allegations that Spanish officials were deploying violent police tactics to stop the spread of COVID-19. His ‘evidence’ turned out to be a video of Algerian riot police attacking protesters.” [3] Albanian newsite, Exit News, “commits itself to independence, accuracy, and honest reporting, we pride ourselves on digging deeper and telling the stories that others do not wish to cover.”[4] Many media platforms are either completely biased or even scared to tackle strong political figures like a Prime Minister for example but not Exit News. By instilling fear in the people he is supposed to protect, PM Rama used a video of Algerian riot police attacking protestors, claimed this was happening in Spain, and then threatened his own people with the same use of force if curfew was broken. Exit News did their due diligence and shared with the people how this video has nothing to do with Spain or COVID-19 and they state “The Prime Minister’s attempts to pass off these images as a government’s ‘normal’ reaction in a time of crisis may be a cause for concern.”[5] Instances like the one aforementioned should all be a cause for concern because it simply should not happen today and it should not happen by someone who holds so much political power.

Case Study #2: Anti-defamation package

In December 2019, just months before the height of the COVID-19 pandemic and PM Rama’s public apology, Albania introduced its “anti-defamation package”, a set of laws that was “supposed to” tackle the fight against disinformation. This package was highly scrutinized by journalists as well as the Council of Europe as it is an “an attempt to muzzle the media while the government countered it was merely regulating “a jungle of misinformation and hate.”[6] So what does the package specifically include?

Simply put by Reuters editor Enton Abilekaj, “This law says ‘if we do not like your news story, we can remove it and fine you’” []. How is this possible in 2021? Easy. When the government itself is heavily corrupt (Transparency International has Albania ranked as #104/#180 in its 2020 Corruption Perceptions Index), then laws are changed and created to benefit those who are in power. Reuters states “Parliament adjusted two laws to empower the Albanian Media Authority (AMA) and the Authority of Electronic and Postal Communications to hear complaints about news websites, demand retractions, impose fines of up to 1 million leke ($9,013.88), and suspend their activity.”[6] At the end of the day, it is all business. As unfortunate as it sounds, these laws were not created for the betterment of the country, rather as a way to censor the media and to make quick money simultaneously.

What happens next?

Just like with every country in the Western Balkans and across the world, fake news and the spreading of it are major topics of conversation where next steps are still being determined. Just two weeks ago, PM Rama declared victory in Albania’s general elections. Even with his public apology and many negative run-ins with the media, he seems to have the public’s support nonetheless. In regards to the anti-defamation package, Dunja Mijatović, the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, stated that the package and it’s newly enforced laws were in urgent need of improvement yet improvement has yet to come. Although every country is different and every case is different, what we can do as constituents is to educate ourselves as much as possible on the realm of fake news and to educate others to ensure that manipulation tactics are not being used to construe our own thoughts and ideas. We here at SLAM are hoping for a better future and it all starts with us.

References:

[1] “Balkan Countries Most Vulnerable to ‘fake’ News: Report.” COALITION OF INFORMATION AND MEDIA USERS IN SOUTH EAST EUROPE. EU-UNESCO. Web. 09 May 2021.

[2] “Albania : Threat from Defamation Law: Reporters without Borders.” RSF. Web. 09 May 2021.

[3] GREENE, Samuel, Gregory ASMOLOV, Adam FAGAN, Ofer FRIDMAN, and Borjan GJUZELOV. “Mapping Fake News and Disinformation in the Western Balkans and Identifying Ways to Effectively Counter Them.” European Parliament. Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies. Web.

[4]”Our Mission – Exit – Explaining Albania.” Exit. 09 July 2020. Web. 09 May 2021.

[5]”Albanian PM Claims Video of Algerian Police Beating Protesters Is Spanish Government’s Response to Coronavirus – Exit – Explaining Albania.” Exit. 21 Mar. 2020. Web. 09 May 2021.

[6] Koleka, Benet. “Albania Passes Anti-slander Law despite Media Protest Calling It Censorship.” Reuters. Thomson Reuters, 18 Dec. 2019. Web. 09 May 2021.

* This designation is without prejudice to positions on status, and is in line with UNSCR 1244(1999) and the ICJ Opinion on the Kosovo declaration of independence.